(Written recently but the story is from 2010 and much has gotten better)

“Are you ready?” Stu asked, handing me a helmet.

“I was born ready” I replied, planting the helmet onto my head and pulling the chinstrap tight.

“Climb on then, let’s go.”

I threw my leg over the large seat of the motorbike and placed my hands on my thighs to steady myself.

“You good?”

“For sure.”

“Cool.” Stu glanced over his shoulder while simultaneously throttling the bike. We were off. We sped through Chiang Mai traffic. Passing along the banks of the outer moat, the city flew by in a blur of sensations. Thick grey smoke from coffee beans being pan-roasted in an alley faded into the overwhelming scent of burning incense from a wat (Buddhist Temple), which gave way to the stink of raw sewage—all of which were infused with the raw exhaust of all the various vehicles in traffic. We passed a foreigner arguing with a tuk-tuk driver, while a pretty Thai woman frantically translated between the two parties. An orange-robed monk walked the streets seeking his morning alms. Children dressed in their crisp, clean uniforms happily strolled to school. It was half past seven in the morning and I was already sopping with sweat. This was partly due to the hot Thai sun, but it was mainly due to the humidity. The kind of humidity that wraps around a body as tight and restricting as moist cellophane; the kind of humidity that is indicative of countries located close to the equator.

The man driving me on the back of his motorbike through the early morning streets of Chiang Mai, Thailand was Stuart Skversky. I had met him nine months prior at one of his fundraisers in Los Angeles. He was a man of girth: ginger bearded, earrings, shaved baldhead, a sleeve tattoo, a dragon tattoo on the side of his skull and an ever-present smile. He was the exact opposite of what I imagined a person going abroad to volunteer would look like. When we met I had stuck my hand out for a handshake, he pulled me in for a hug and said, “What’s up homie?” We were instant friends.

Up ahead a traffic light turned from yellow to red.

Rolling to a stop Stu asked, “You ready for this?”

I wiped the steamy perspiration from my cheeks. “I am. I know it won’t be easy, but I’m ready.”

“Just remember what I told you”, he reiterated, “You’re gonna see some things that are downright beautiful and some things that are gonna make you want to weep like a baby.”

The light turned from red to green. Fifteen minutes later Stu steered the motorbike down an unpaved road. Gravel crunched and popped under the weight of the bike. Slowly we crept through the gates of the orphanage he volunteered at, Wat Don Chan. He stopped the motorbike in front of a nondescript concrete building. A flock of smiling kids, I judged to be about six to eight years old, were playing outside in the heat. When the children saw Stu they stopped playing their games and immediately swarmed him. They hugged Stu and tugged on his shirt for attention. One boy swiftly crawled onto his back and hung his arms around his neck. Stu toted the boy around while happily acknowledging every child in his presence. He introduced me to his fans one by one. He told me their English names, names like Bob, and Apple, and Soda—names they had picked out themselves. With those names came the story of each child, and the horrific circumstances that brought them to the orphanage. I heard stories of abandonment, family death, and of parents too destitute to care for their children. Yet in each of their dark tan faces I saw light. I saw love. I saw hope.

We walked past an elaborate wat decked out with ornate carvings, numerous tapestries, and multiple Buddha effigies. Outside the wat were massive statues of Buddha, Ganesh and another deity I was not familiar with. Each statue was painted in garish tones of gold and red, and on each statue laid multiple strands of bright flower necklaces. As the throng of children dissipated into various classrooms Stu led me further through the grounds of the orphanage. He first showed me the school building, the newest building on the premises. The classrooms were similar in size and shape to other classrooms I had been inside of in America, the real difference was that the children were alert and attentive, hanging onto every word spoken by their teachers. They drank in their lessons the way a dehydrated man gulps down water at an oasis. The computer lab was outdated and the building was absent of air conditioning, but that did not deter them. The children were there for a purpose and they did not squander the opportunity.

Our next stop was the boy’s dormitory. A beige building that had seen better days, it was a three-story affair with scarred walls, chipped plaster, and screen-less windows. The first floor housed the young boys, boys from the ages of three to nine. It was lined on both sides with bunk beds, leaving a narrow space in the middle to walk through. Each bed was worse than the next, with mattresses that were either so rotten their rusted springs peaked through, or mattresses that were cardboard thin and looked to be held together by prayer alone. The boys lived in squalor. Piles of trash and dust and soiled clothes were littered throughout. The worst thing about this dormitory, however, was its smell. The putrid stink of stale, musty urine hung heavy in the air.

“Why is this place so trashed?” I asked, my heart burdened with concern.

Stu sighed. “Yeah, it’s pretty disgusting, right? There just are not enough monks to take care of everything and pick up after these little guys. They make each floor responsible for themselves and the sad part is these boys just are not old enough to take care of themselves. Lice is a big problem down here, too, that’s why you’ll notice all of the young boys have their heads shaved.”

“How many kids are there? How many monks are there?” My questions came out in rapidfire succession.

“There are about seven hundred and forty kids and only seventeen monks, and me, and a couple other volunteers.” As I looked around at the filthy conditions I could not fathom having to fend for myself at their age. The harsh reality of their lives became very real.

The second floor was in a slightly better condition. I was told that the boys on that floor ranged between ten and fourteen. There was less visible garbage. There were still no screens on the windows and despite some of the beds having mosquito nets, the huge, fist-sized holes in the netting them made them utterly useless. The smell was slightly less obnoxious as the boys that lived on this floor were able to look after themselves better than the younger ones. That floor, too, was lined with bunk beds, and the mattresses, if you can call them that, were also in a state of disaster. Some mattresses sagged so low they bent like a bow. Some beds had mattresses that looked as if you would need a tetanus shot just to get a good night’s sleep. And some bunks did not even have mattresses at all, merely a blanket laid on the chain-link-like bed frames.

“How do these kids sleep like this?”

“My guess is”, Stu said, his tone low and solemn, “they don’t, and if they do, they don’t sleep very much. That’s one of the projects I’m working on right now is getting donations for mattresses. My goal is to get a new mattress for every single one of them.”

The third floor of the boy’s dormitory was the best floor. It housed boys aged fifteen to eighteen and it was remarkably clean. Only occasionally would a waft of foul-smelling air come up the stairwell from the lower levels. Again, the floor was full of by bunk beds, but some of those beds did have new mattresses. That was a slight relief.

The Orphanage – Part 1, By: Charles R. Vaught Jr.

OK so my buddy Charles is a writer, fisherman, fire fighter, student and all around good dude. I asked him to write a 2 part story about this experience from his first trip to the Wat. He lived here for a couple of years and I am sure that his feelings may have changed since writing this, I know mine have.

You see culturally Thailand is a very different place than the United States and I am sure many other countries too. When I got here to Chiang Mai and moved in to the Wat, which I lived in for 2 years, I was like WOW! Now that I have lived here for 6 years and been to many Hill Tribe villages, temples, orphanages, etc., I see things differently. Although sometimes I do not agree with everything that I see at the Wat, I at least understand why things are done the way they are. Above is part 1 of Charles story, stay tuned for part 2, coming soon.

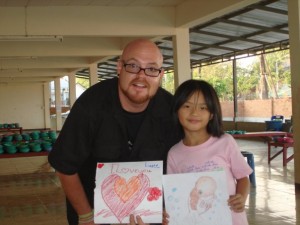

The picture above is of Charles and myself with some super happy kids from a Karen Hill Tribe village, a 5 hour drive from the city. We spent the day giving out things that were donated to us including frisbees from the Long Beach State Frisbee team and played games with all of the kids, it was a blast.